I Devoured This Book

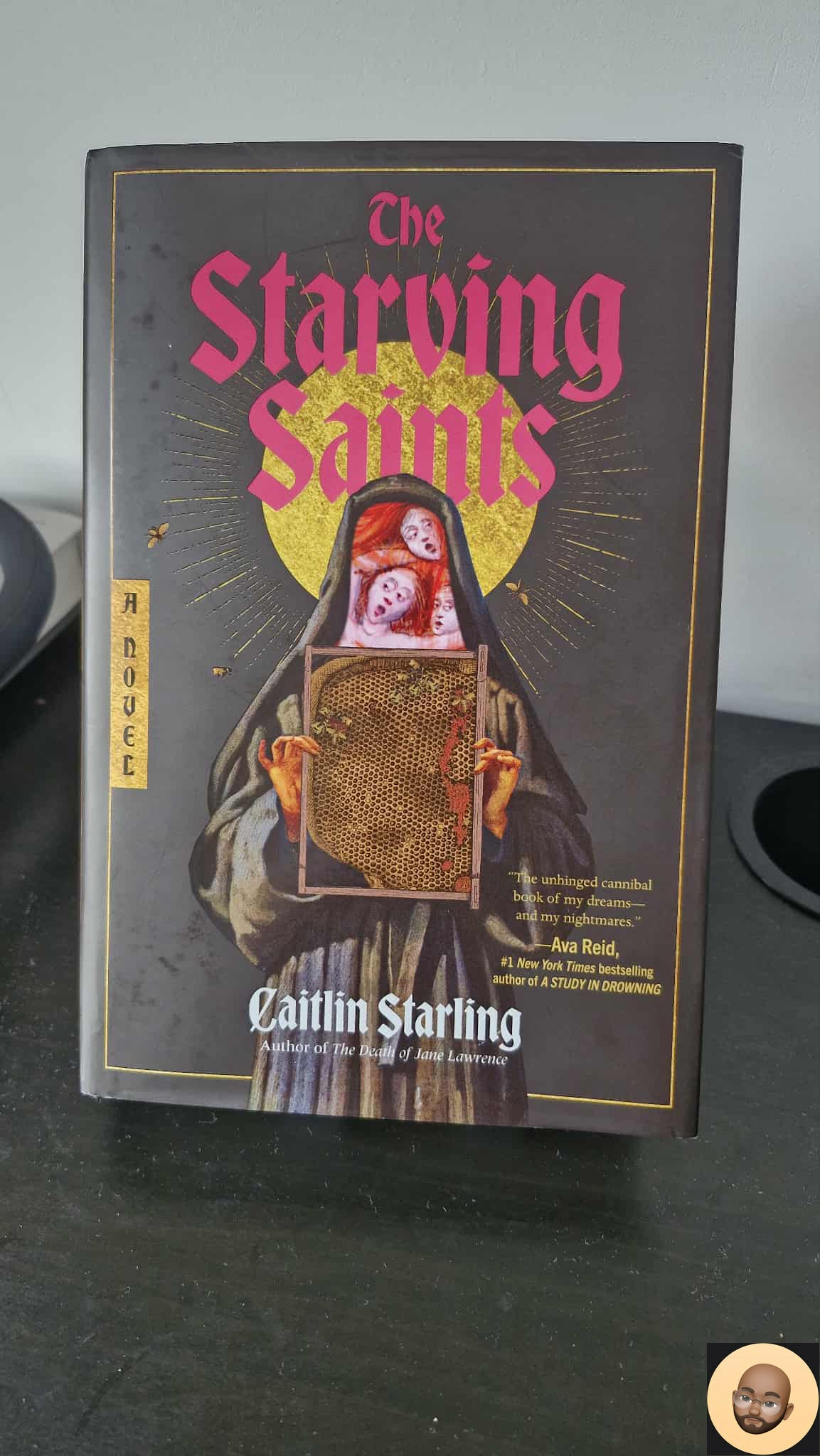

A review of "The Starving Saints" by Caitlin Starling

“Maybe faith, when brought to life, is too much when you’re drowned in it your whole life.” - Caitlin Starling, The Starving Saints

Imagine this: you are trapped in a medieval castle with your king and your lord. There are around a thousand of you. The fields which you relied on for food are outside the castle’s walls. The royal gardens within the castle are bare. You only have 15 days worth of food left. And no one is coming to break the siege.

This is the premise of the novel “The Starving Saints” by Caitlin Starling, and boy did she run with it, and then some. The novel explores the effect of hunger on people — how far it will push them, and whether starvation can break a person’s sense of right and wrong. It is rightly set within the walls of a medieval castle taking advantage of the complicated relationships among lords, peasants, and the priory.

The story is told from three third person viewpoints: Phosyne, the madwoman of the castle who is charged by her lord and the king to produce miracles for them; Ser Voyne, the king’s most beloved knight (yes, she is female) who has now been turned into a useless showdog (I cannot help but picture Gwendolyn Christie whenever Ser Voyne appears); and Treila, a maid who is actually more than what she seems.

Together, these three women tell the story of how a besieged castle’s inhabitants go mad as they find themselves trapped and starving. Their situation is made worse when the saints they prayed to for deliverance show up at the castle gates and begin conjuring bacchanalian feasts every night, with only the three women able to see what’s really going on, and what’s on those endless platters of food that the inhabitants consume.

Starling deftly weaves the three viewpoints and we are given access to all the important events in the castle. We see how the lords and their favored people are given more food while they try to tackle ways by which to break the siege or ask for help. We see how the rest of the inhabitants are made to look for the last remaining rats so they could feed themselves, while waiting for their lords to deliver them from this nightmarish scenario. We even see how Phosyne is tasked with delivering miracles after she managed to cleanse the waters of the castle, but even that is not enough anymore.

Which brings us of course to the quote that I started this entry with because just before their food was about to run out, the saints that they had been praying to fervently for relief, finally manifested, and it seemed that all their problems would be solved. But these saintly manifestations are cruel and also driven by a different form of hunger - total submission from the king to the lowest servant. That becomes the price for dealing with them - the abandonment of one’s will. The more the people of the castle feasted on the food being served to them by the saints, the more their wills got obscured and they become nothing more but automatons who are able to carry out the most cruel of demands just to continue eating.

That quote is what I consider the punchline of the novel. Whenever I read fiction, I always try to look for the statement that ties everything together. It’s what we used to call the quotable quote - short, sharp, and sweet. And indeed, this novel is also a musing on faith and its opposite attribute doubt. Many of us were raised as people of faith. We did not choose this as children, but we were made to believe in fantastical things and to forego proof because doing so would be sacrilegious. We live our lives of faith hoping all of it would eventually pay off, that there’s a reward for believing. It makes it easy for us to dismiss the rest of human suffering because we can always claim: they didn’t believe, or they didn’t believe correctly (as if the way we believe is correct). And thus, we end up with all these prejudices simply because our version of that faith demands it, because we fear that if we stray from its teachings, we too will be starved of the blessings that are somehow controlled by unnatural forces.

Phosyne and Treila immediately see through the saints’ ruse but are unable to convince everyone else. Voyne, on the other hand, knows that something is fundamentally wrong, but her blind loyalty to her king overrides her own will. Her desire to be loved and be treated as the heroine that she is makes her vulnerable to the machinations of the saints. And it is up to the other two women, both of whom have conflicting agendas when it comes to Voyne, to convince the once-esteemed knight to break out of her old bonds, because ultimately, her devotion doesn’t really belong to the king or even the saints, but the people of the kingdom she had vowed to protect.

There are times when this novel feels ponderous and its characters stupid, but in the context of the world, they are both necessary to make the point that many people will do anything for their faith. Even the priory, which recognized the saints for who they really were and was supposed to be the authority in all things religious, were ignored and supplanted by the saints who managed to provide immediate relief, even if those comforts were done under false pretenses.

It takes a while to get fully invested in the story, especially if you have been used to singular points-of-view stories and novels. But Starling is skilled enough to handle the viewpoint transitions, that by the time the saints arrive, it’s hard to stop reading. The level of detail she used to dramatize the woeful castle’s state and its occupants will transport you to an era filled with disease, desperation, and yes, hunger. Which in turn, allows the motivations and actions of its three protagonists to shine more brightly.

The novel is really a delightful twist on the old saying “be careful what you wish for, you might just get it.” And as these characters find out, all wishes have a price. The real question is, would you be willing to pay that price no matter what.